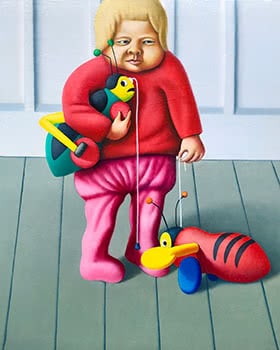

Chris Cricket Meets Buzzy Bee

74.5 x 60.5 cm

est. $100,000 - $150,000

PROVENANCE

Collection of film maker Tony Hiles,

Wellington

ILLUSTRATED

p 56 Michael Smither Painter, Trish

Gribben, Ron Sang Publications 2004

Chris Cricket Meets Buzzy Bee can be viewed in various ways: as a lens into the artist's family life, as an example of Michael Smither's unique painting style which was contributing to a new language of New Zealand modernism, and of course, as an essential piece of Kiwiana.

In the initial years following Smither's graduation from Elam in 1960, he proved himself a bold and experimental artist, and started to identify themes and forms which would be central to his work for decades to come, for example, rock paintings. Given that he was at such a formative stage in his career, the 1960s would have been a watershed moment for Smither regardless of what was going on in his personal life. However, the birth of his children gave sharp focus to this period of his artistic production, and he dedicated himself wholeheartedly to capturing scenes of domestic life.

Many of Smither's best loved works come from this time, including a number of large scale oil paintings that examine the joy and energy - as well as the more mundane aspects - of his family life. It is interesting that the word 'chaos' is often used to describe these paintings. Sometimes the word's application is straightforward - children fighting, tears and moments of tension certainly deserve the term. It may also be because this is one of the few words which effectively capture the frenetic, immediate energy with which Smither was painting these domestic scenes. 'Chaos' reminds us of his status as a parent and participant in these scenes, it also lends a sense of implication, responsibility and mischievous collaboration.

This portrait, of Smither's daughter Sarah, is a perfect example of the special, personal tone of these works. The little girl's interaction with her two toys - Chris Cricket and Buzzy Bee - and her sly, impish expression reflect the openness of a conversation in which the artist is fully present. It is clear that Smither was not merely observing the child in the capacity of neutral artist, but painting a visual dialogue which reflects his own love and involvement in his daughter's life.

It's impossible to resist the wit and charm of this scene. Through it, we glean some sense of Smither's sense of humour. Take, for example, the lines of Sarah's pants which are bunching around her nappy in that particularly toddler-like way, a detail executed with such serious and perfect modulation that it seems almost comical. Or there's the helpless, terrified expression of Chris Cricket as he's tucked under the child's arm. This is just a tiny detour from reality, but it opens up the painting in a new way yet again, inviting us into the mind of Sarah and her childlike imagination.