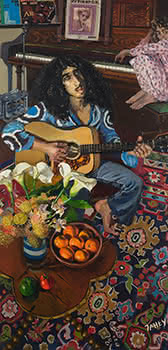

Rob Plays the Blues c.1979

121 x 58 cm

est. $25,000 - 35,000

PROVENANCE Barry Hopkins Art Trust Collection

EXHIBITED Barry Lett Gallery, June 1979

Exhibited at the artist's solo exhibition at Barry Lett Gallery in June 1979, this painting skilfully combines figures with musical instruments in a domestic interior for a modern twist on a traditional subject from art history. The main focus is on the figure of the young musician who is playing his guitar behind the coffee table, his soulful face framed by thick black curls, but still-life objects also compete for our attention.

The mood of the painting is sombre despite its bright colouration. Rob's youthfulness is countered by his serious expression as he gazes up to his left, seemingly searching his memory as he fingers the strings of his guitar. Clothed in classic '70s fashion, a tie-dyed blue shirt and denim flares, his head is turned, directing our attention to the elfin figure of Emily, the artist's youngest daughter, who perches on the piano stool behind. Her figure is cut off by the frame like a Degas ballet dancer, but she looks directly and purposefully at the viewer, while her left hand reaches towards the black keys of the piano. Just 12 years of age when this painting was made, Emily would go on to study music and become a professional singer in later life.

A short history of American influences on post-war music is provided by the references in this painting. Emily's pink frock, sprinkled with flowers, shares its tones with the cover of the sheet music from the 1944 American romantic comedy My Pin Up Girl, featuring the movie's star, Betty Grable. Beside Betty on the music stand to the left is displayed the sleeve of the 1955 LP Satch Plays Fats: The Music of Fats Waller with a close-up portrait photograph of the recently deceased trumpeter Louis Armstrong (1901- 1971) on its face.

Newsprint is collaged to the surface of the image under the text which gives us the name of the record, recalling Fahey's earlier interest in Synthetic Cubism. Like the French artists such as Georges Braque who glued newsprint to their works to emphasise the fabricated nature of the composition, she is showing how art has moved on from being a window onto the world and can now provide a commentary on it. A six pack of beer cans tucked in beside the piano leg acknowledges the revolutionary imagery of Pop Art, where artists like Andy Warhol painted Campbell's soup cans in a homage to the art of advertising, in recognition of how it had infiltrated everyday life in 1960s media-saturated America.

The information conveyed by the specificity of these products contrasts with the generic nature of the way in which the woodgrain veneer of the upright piano has been painted. Like the inclusion of the bobbin-legged table in the foreground, the representation of the patterns in the wood grain of the piano reveals the artist's admiration for the craftsmanship of Victorian vintage furniture which she collected and used to create a home for her family. The light blonde ash veneer of the body of Rob's modern guitar stands out, bracketed by two dark stained examples of colonial furnishings. Similarly, Rob's Maori whakapapa distinguishes him in Fahey's depiction, and so do his green eyes. He is at ease amongst the accoutrements of settler culture, playing the twelve-bar melancholic sequence of the blues, developed by black American musicians.

There is a shift in perspective between the figures in the centre ground, and the still-life components which are arranged on the clover-leaf top of the gypsy table in the foreground. This is tipped up towards the viewer so that we can enjoy the light reflecting off the glossy skins of the oranges, and admire the way this colour contrasts with the bands of electric blue characteristic of Cornishware on the jug holding a mix of arum lilies, yellow waratahs and Japanese irises. Fahey also demonstrates how the complementary colours red and green work in proximity by placing a tomato and green apple together on the table. Foreground and figures are brought together by the vibrantly patterned Persian rug, its bright colours enlivening the floor and repeating the blue theme of the work. This carpet is familiar to viewers from many of the interior scenes she re-created in paint during the decade Fahey lived in a house in the grounds of Carrington Mental Hospital where her husband, Fraser McDonald (1924-1994 ) was Medical Superintendent.

In her second volume of memoir, Fahey explains her turn to her home and family as subjects for her work: ... after my father's death I was gripped by urgent pull. I understood my immediate life was my inspiration. The mess on the table, the dishes, the unmade bed, all took on an aura of profound meaning. My mother visiting, the gardener working outside, the children eating, drinking, thinking. When these paintings were exhibited, I was called a domestic painter - but domestic painters in the past had tidied up their houses first, or, I assumed, their wives had. I was making the mess visually lovely, taking the gentility out of the genre.

Linda Tyler