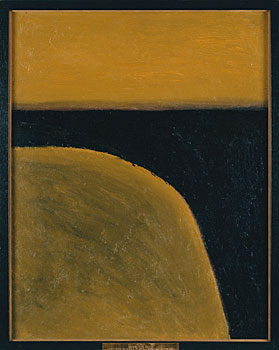

Small Landscape

54.5 x 43.4 cm

est. $40,000 - 60,000

PROVENANCE

Doug and Nane Green Collection, New Zealand until 1978

Gifted to ICI New Zealand Collection, ICI label affixed verso

ICI Collection became Orica Collection, Australia

Orica label affxied verso

Sotheby's Australia, 26 August 2002, Lot 531

Deutscher~Menzies, Fine Australian & International Art, Sydney 13/03/2007

Savill Galleries, Sydney, NSW label affixed verso

REFERENCE

Colin McCahon online database cm001474

In Colin McCahon's 1964 Small Landscape, sublime rawness is borne by painterly abstraction. Though this may be a relatively modest-sized work, it immediately arrests the viewer's attention and compels a process of dynamic meditative dialogue and exchange. Herein, McCahon's mastery of the New Zealand landscape is beautifully exemplified. By virtue of the sheer force of his spiritual connection with the land, he has succeeded in articulating an impression of Northland. Speaking of his landscape paintings, McCahon described his intention as to "throw people into an involvement with the raw land, and also with raw paint ... like spitting on clay to open the blind man's eyes"; these words certainly resonate when considering the present work.

Small Landscape comes from a deeply personal place for McCahon, and shows that he was capable of realising that which great American Abstract Expressionists such as Mark Rothko were striving for at this time, i.e. marrying something from within his deep subconscious to the land, through a self-aware process of psychic automatism. The internal struggle from which this sublime painting was created is perceptible in the work's three solid forms, which collectively offer something of an oxymoron: the clear delineation and forceful presence of the primal, pared-back landscape, which has been stripped of all extraneous detail to endure as a vibrant colour-field, seems on one-hand to be unshakeable in its permanence. At the same time, however, the relationship between the land, sky and void is complicated, and there is a certain ambiguity in the attribution of an earthy pigment to the form which would otherwise been presumed to represent the sky. This compels the viewer to grapple with a shifting reality where tangible landforms and intangible abstractions collide. Further, almost instinctively, one becomes absorbed into the void piercing the centre of the canvas which, interrupting the flow of sky and land, draws comparison with Barnett Newman's zip paintings. The importance of that void, the darkness, lies in what it does not represent; the associated idea of nothingness is one which instils the work with a creationist essentialism.

The 1960s represents a crucial period in New Zealand's art historical development: the need for a modern visual identity and relevant artistic language was being keenly felt. Small Landscape is important in that it serves this end by communicating a language of universal creation, spirituality and transcendence in purely New Zealand terms. Where else are we able to encounter such unbridled grappling with the essence of our existence in a way that draws on our own familiar and precious landscape?