Baptism, After Piero: An Adaptation, 2003

90 x 60 cm

PROVENANCE Private Collection, Dunedin Purchased 2003

ILLUSTRATED Don Binney: Flight Path, Gregory O'Brien Auckland University Press, 2023

The lone bird which characterised Don Binney's greatest paintings from the early 1960s onwards was always, in his mind, an emissary or embodiment of spiritual values. Early in his career he was influenced and inspired by the bird-motifs he saw in Maori rock art (it was Theo Schoon who introduced him to this tradition), as he was by the Sun-Bird-God symbol he discovered in pre-Columbian art from the Americas. Importantly, in his mind, the lone bird hovering above the firmament was also the Holy Spirit of Christian tradition. In early paintings such as Pastoral, Te Henga (1965-66) and Tabernacle (1966) he consciously posited a piwakawaka in the role of the Holy Spirit. His art sought to find an accommodation for Christian tradition within the indigenous culture and natural history of Aotearoa.

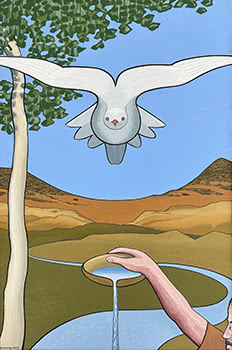

Perhaps the most overtly 'Christian' painting in his oeuvre, Baptism after Piero: An Adaptation is - as the title tells us very specifically - a meditation upon and revision of Piero della Francesca's masterpiece The Baptism of Christ from the mid-15th Century. Binney's 'adaptation' has its origins in the time he spent living in the United Kingdom. 'For much of 1972-3,' he wrote, 'I was living in London and became familiar with Piero della Francesca's Baptism of Christ in the National Gallery collection. I absorbed much of the painting's presence and attributes, rather than scrutinising it...'

Binney clearly felt he was partaking in the spirit of the work rather than trying to deconstruct or analyse it. At the same time - and over the years that followed - he paid much attention to the 'golden section' and other formal aspects of Piero's work. 'Piero della Francesca's "Baptism" is an immense and multiple visual narrative,' he wrote, in notes dated 2003. 'The descending dove of the manifest Holy Spirit seems to visually slip into the space directly above the Baptist's right hand, which in turn tips a bowl from which the Jordan water pours ... onto the head of Christ.'Binney consciously took the elements of the dove, the hand and the flowing water from the Baptism: 'I also borrowed and repositioned other features of Piero's painting ... Working studies explored the transition from della Francesca to Binney in linear terms. The final work sought to transcend those linear notions out into a resolution of paint surfaces in my own signature.'

The lone bird always carried a myriad of associations for Binney. It embodied a state of grace, transcience, independence of spirit, freedom, aspiration, the flight of the soul after death ... He knew well, from school years, the multitudinous birdlife manifest in Romantic poetry (from Shelley's 'Ode to a skylark' to Coleridge's albatross-tale) yet he always made a point of stating his artistic allegiance to Classicism rather than Romanticism, as such. His paintings were meticulously thought-out and executed in the 'classical' tradition. While there were discoveries along the way, and some necessary painterly happenstance, he took pains to plan/organise his works in advance- more so as he grew older.

Baptism might be one of his most assiduously planned works. Using the schema of Piero's work as his template, he made a number of pencil studies, gridding up the Holy Spirit/bird and fine-tuning its wings and tail-feathers. With similar exactitude, all aspects of the composition were adjusted. The painting might also be his most overt statement of faith. As elaborated upon in the forthcoming monograph Don Binney-Flight Path, Don Binney was a practising Anglican through most phases of his life and, during the last two decades, he became a lay preacher and parishioner at St Albans Anglican church in Balmoral.

Yet the relevance of this painting extends well beyond any conventional notion of Christianity. Binney's faith was, by his own account, essentially holistic and stretched beyond the human realm.

He believed that birds, animals, trees and other elements of nature were in a direct relationship/ communication with the divine. In this personalised 'adaptation', the bird is the over-riding presence- balanced, caught in an upstream, overseeing-while elements of earth, water and air are abundantly present. The human presence-so assertively present in Piero's originating work-has here been relegated to the outer edge of the image. The viewer is left with a scenario which is almost Zen-Buddhist in its reductivism, which is both devout yet ardent in its non-conformism.

GREGORY O'BRIEN